Persevering in Powerlifting & Navigating Low Motivation

I’ll be the first person to tell you that my love for lifting has been tested at times; that showing up has gotten hard, many times over. But that said I have consistently resistance trained for over ten years now. A few breaks for travel, but otherwise 3-4 days per week for the last ten years.

I’ve not always trained extremely hard, I’ve not always trained for a heap of hours at a time, and lifting has not always been overly salient in my life, but I’ve always showed up. And because of that fact I have continued to improve — improve my skill, improve my strength and improve my toughness in persevering through those harder periods.

There are a few tools, strategies and trains of thought that I’ve adopted over the years to stop me from losing my mind when I feel like I’m falling out of love with lifting. Right now I’m feeling pretty disenchanted with training. That’s been the case for a few months now. But never do I catastrophise and think that my powerlifting career is coming to an end; and never do I throw in the towel and stop training altogether. Here is what helps me with that.

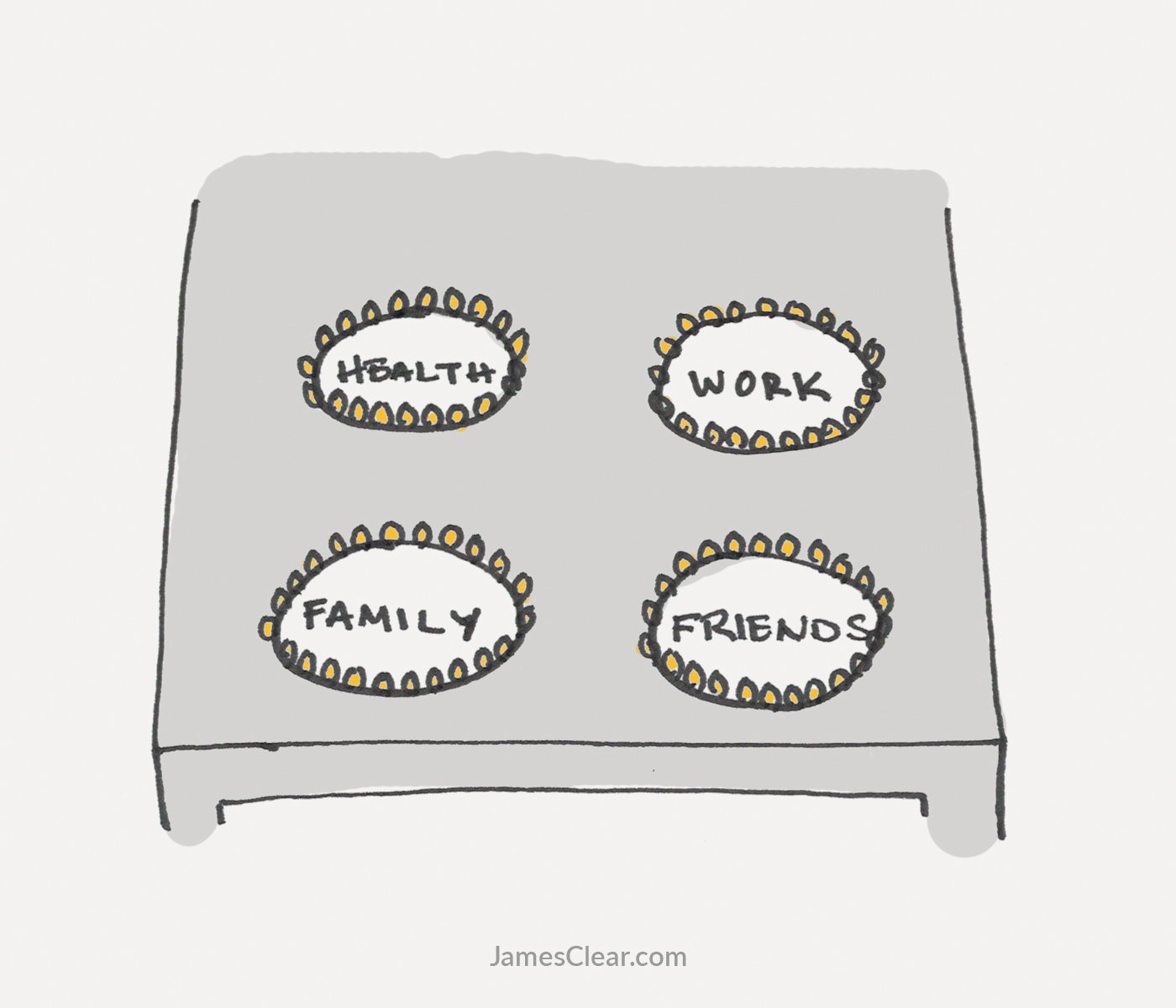

“The Four Burners Theory”.

I love this by James Clear. You can read about it at length here.

The basic premise is that your life is represented by a stove with four burners. Each burner symbolises one major quadrant of your life.

The Four Burners Theory says that “in order to be successful you have to cut off one of your burners. And in order to be really successful you have to cut off two” — because life is filled with tradeoffs. If you want to excel in your work, then your friends and family may have to suffer. If you want to be healthy and succeed as a parent, then you might be forced to dial back your career ambitions. Of course, you are free to divide your time equally among all four burners, but you have to accept that you will never reach your full potential in any given area.

James Clear’s “four burners theory”

We can think of sport/powerlifting/our athletic endeavours as representing one of these burners. Particularly if powerlifting is a big deal to you, it is not wild to think that it can demand it’s own entire quadrant. If you want to allocate significant time, effort and energy to powerlifting, other parts of your life will need to be dialled down. But similarly, if uni, work, business, family or whatever else needs more of you at a given time, perhaps powerlifting needs to be dialled back.

Often times for me and the people that I coach, our lack of motivation for powerlifting stems from competing demands elsewhere. Hauling my ass to the gym for 90 minutes feels like a slog when I’m trying to set up my business to permit me to travel for a year, when I’m working on a visa application, when I need to rent out my house and sell my car and find somewhere for my cat to live.

Just this week one of my clients purchased her first home. Training has been a little uninspiring for her recently, while she’s been making a huge life decision, constantly in conversation with her mortgage broker, banks and her husband about something so life changing. Lifting has been dialled down for both of us so we can turn the heat up elsewhere.

One of James Clears’ approaches for thinking about the four burners theory is to embrace the seasons of life — I love this approach a lot.

“Commit to your goal with everything you have — for a season”

Over the two years of lockdowns in Melbourne, I poured myself in to powerlifting. Travel, my family, my work were all dialled back by circumstance, which meant I could really turn up the heat on my training. Now on the other side of lockdowns, I am excited to travel, be with my family and experience more of life. I am still gonna lift, but the heat will just be turned down there.

You can decide how long your seasons are — perhaps they’re a few months long for a university semester or a competition prep; perhaps they’re years long while you start a family. In any case, when we can view life as having seasons, we can reduce the pressure on ourself to succeed at everything all at once. And instead just give the effort we have available at that time — however little or much that may be.

You don’t have to train 4-5 days per week or bust.

You can turn the dial down on powerlifting without cutting it off altogether. Is one session per week better than none? Absolutely. Are two sessions better than one? Almost certainly. Are three better that two? Most of the time. Are four and five better again? Maybe, under specific circumstances, but certainly not always.

The point: a frequency of 2-3 sessions per week is perfectly adequate and productive. Perhaps right now you can’t or don’t have the heart for an intense training week. That is okay! It’s absolutely not necessary.

But viewing training as on or off in these circumstances is rarely productive. “Either I train 4-5 times or I do not train at all”. This attitude just fuels inconsistency. Inconsistency is the killer of gains.

I have been training 3x per week for all of this year. Is that gonna make me a world champion? Of course not. But will it keep me moving forward, enjoying my hobby, spending time with my friends? Yeah, it’s doing that perfectly. To be honest, at this point in my life I don’t see myself training 4x weekly ever again. But even more than that, I can’t envision a life without lifting — which is what adjusting my training and my expectations has given me.

If you’re feeling disenchanted by training or life is pulling you every which way — dial your training right down rather than cutting it off altogether. You’ll better retain your muscle and skill, you’ll maintain the habit of showing up for yourself and you’ll be much better positioned to launch an assault on your training again when you’re more able or more inspired to do so.

Similarly, your sessions don’t have to be hours long. 45 minutes of quality movement can be great.

We rest a lot in powerlifting. We’re also fucking chatty. So naturally, there is a bit of a culture around really long sessions. And certainly, the best of the best do train for hours at at time, most of the time. But do we as recreational powerlifters need to mimic that year round? Absolutely not. And do we need to engage in training that demands long rest periods? Also no.

Drop your heavy top sets for a while, use machines that require fewer warm ups, super set, create circuits, shift towards a hypertrophy focus. Again, if you don’t have the time or the heart for long sessions, don’t do them. But there is a huge grey area between not training at all, and training 4x sessions per week for two hours at a time.

Train twice per week for 45 minutes. Put your headphones in and your head down and you’ll be surprised with how much you can get done.

Train with intensity and don’t faff around.

If you’re feeling uninspired by the gym then dragging your sessions out to be longer than they need to be will not help. Set a timer and the goal to get in and out of the gym as quickly as possible. Have your session written out, restrict your rests, avoid a heap of chat and just get it done. Your training will feel like less of a drain if you’re not dragging it out longer than you have to — particularly if training is feeling like a drain because you would rather spend your time elsewhere.

Have a break from the powerlifts.

You do not need to squat, bench and deadlift year round. In actual fact, once you’ve got the skills down pat they’re rarely the most productive use of your time. People can be so resistant to breaking from the powerlifts. Like they’re gonna lose their strength if they’re not performing one specific exercise. The powerlifts are demanding, taxing, require a heap of warming up and can demand a lot of rest time.

Alternatively, variants can be performed quicker, at lighter absolute loads, with shorter rest periods and can fatigue you notably less — leaving you with more energy for more important things.

Pendulum squat, smith machine squat, split squat.

Dumbbell press, incline bench, machine press.

RDL, good morning, hip thrust.

There are other exercises available to you to train the main movement patterns that won’t make your training such a grind.

Personally, I perform my competition style lifts for about 12 weeks per year leading in to competitions. They’re fatiguing and they make my body hurt. And yet, I still train for powerlifting year round. I train variants of the powerlifts that feel good for me and that allow me to train hard, free from injury and fatigue that I can’t recover from.

“You can train for powerlifting without training the powerlifts — at least for a season.”

Remove the exercises you don’t like.

There is no single exercise that is absolutely essential year round. Don’t like conventional deadlifting? Don’t do it. Don’t like split squats? Take a break. If getting to training right now is already challenging you, building your sessions of shit that you don’t like is probably not going to be the key to reigniting your fire. Make requests to your coach and have your program built out of exercises that you actually enjoy doing.

When I am feeling fussy about my training, I’ll send my coach a full list of exercises that I’d like him to build my program from. As long as you are training some key muscle groups and movement pattens, the specifics of your program don’t matter. And certainly, training some exercises is better than training none at all. Better for you to refuse a split squat than to refuse training altogether.

Do other things that you enjoy.

Be open to distracting yourself from powerlifting for a bit. Be attentive in your sessions + get them done. And when you’re not in the gym, do things that do light you up, where you are right now. You don’t need to be an all-in, full-time committed athlete year round. You’re allowed to enjoy and be distracted by other things too.

Most of all accept that powerlifting doesn’t need to be front and centre in your life at all times. In fact, it shouldn’t. Family, friends, work, study, hobbies, travel should and will be more salient in your life across the seasons. A lull in motivation or some competing priorities needn’t mean that you throw in the towel. Manage your expectations of yourself and your training and make some adjustments to your approach. That way, when life is such that powerlifting can enjoy more of your attention again, you’ve got the habits, momentum and base to support that.